by Chelsea Oware

It is very easy to write about certain experiences when your mind is completely separate from the object of interest. It almost seems intelligent to detract one’s personal emotions from their work, for objectivity purposes, obviously. But, perhaps, that is not always the wisest choice, especially when one is inclining towards humanitarian work or humanitarian research.

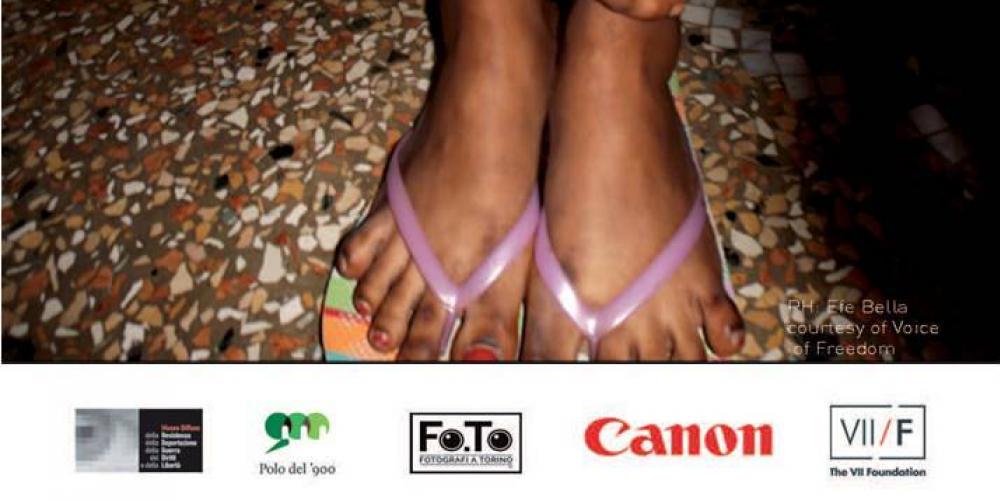

I personally received a loud and clanging, yet timely, wakeup call on the 23rd of June, when a colleague and myself attended the Voices of Freedom exhibit, curated and directed by Leila Segal to shed light on the horrors faced by Nigerian women who are trafficked in Libya, and enslaved, and then forced to migrate to Italy on unsafe, overcrowded boats, and further forced to participate in forced sexual labour, abused and harmed in more ways than one. Photographic activism – the only way to describe it.

The exhibit consisted of numerous photos curated and captured by women who faced the atrocities, using pseudonyms to protect their identities, of everyday activities and objects that represented aspects of their journey, of their pain and of their growth. According to Segal, the participants were taken through workshops to work through their emotions and discover ways to convey them through photography. The fact that daily activities served as a reminder of the difficulties faced does not only demonstrate the deep psychological impact of the ordeals faced by the victims, but also their immense strength as they power through every day, constantly facing reminders of their pain.

Trying to maintain objectivity when researching racially motivated targeting, and issues facing women of colour, particularly from the African continent can force one, especially when one is hardly different from the subjects of investigation, to alienate their feelings from their work. However, that acts as a double-edged sword as one’s investigation remains two-dimensional, flat and without feeling. And, even if one could somehow allow for their emotions to intervene in their research, unless one has been directly faced with the situations on which they write, they can never directly and fully know and feel enough to tell that story.

This is why the work of conscious photography and art is so essential in academia, in progressing towards a more human solutions towards crises – because humans are involved in crises and subtracting humanity from crisis-solution creates more crisis.

For me, the work of Segal and this brave band of women allowed me to perceive what I could not directly see, to the brink of bringing to me to tears – uncontrollable tears. There are realities that I cannot face, as an academic and as a woman, and not to romanticise them in the least, but the fact that someone could and did, and decided to convey them bravely and confidently through art and language, allowed me to feel and understand the subject matter far deeper than I could before.

News and social media often talks about trafficking and modern-day slavery, the world for a moment was absolutely shocked and gob-smacked at the discovery of slavery in Libya, that still continues to occur in 2017, there is media everywhere that warns of sex trafficking and forced migration of women and children. While these are substantial moves in creating awareness, it is often repeated that the world is becoming more and more desensitised to crisis due to the normalisation of these campaigns. The world nary hears of the effects of these crises from the victims themselves. The work of these women, forcefully and unconventionally conveying this crisis has confidently imparted the necessary message without portraying the women who faced it as victims, but as strong, powerful, superhero women; as survivors.

The author's concepts and ideas promoted in this contribution are his own and do not necessarily reflect the view of the CSA.